View or download a PDF of a recap of the event here

Americans for Financial Reform, together with Better Markets, welcomed Anat Admati, Professor of Finance and Economics at the Stanford School of Business, together with esteemed panelist, Assistant Professor of Business Law at Michigan Ross, Jeremy Kress, to discuss the recent update to Anat’s co-authored book, The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do about It, which debunks myths about bank capital.

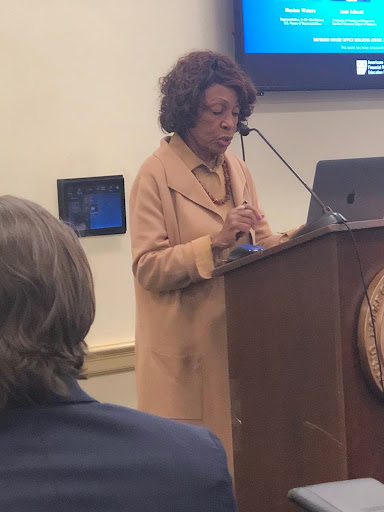

Ranking Member Waters introduced Anat and Jeremy, reminding participants that it has been a year since the 2nd, 3rd and 4th largest bank failures in U.S. history. Waters noted, “while our regulators are working to strengthen capital requirements, those oppose d are working overtime to block that effort, peddling lies about what credit capital reforms will do, going as far as taking out expensive television and social media ads and setting up a website filled with misleading claims. They don’t want you to know that the only people who benefit from lower capital requirements are wealthy bank executives.”

d are working overtime to block that effort, peddling lies about what credit capital reforms will do, going as far as taking out expensive television and social media ads and setting up a website filled with misleading claims. They don’t want you to know that the only people who benefit from lower capital requirements are wealthy bank executives.”

“Less [equity] capital means consumers are left more vulnerable, especially in a downturn, while bank executives take home larger bonuses every year. Lower capital requirements also mean taxpayers are more likely to be called to bail these banks out when they run into trouble.”

“[Equity] capital is not a thing that gets locked away, rather it is a source of funds like deposits that banks are able to redeploy. In fact, better capitalized banks lend more than other banks, in good times and in bad. Our presenters help set the record straight about how higher capital levels will prevent future financial crises, while ensuring consumers looking to build wealth can access credit.”

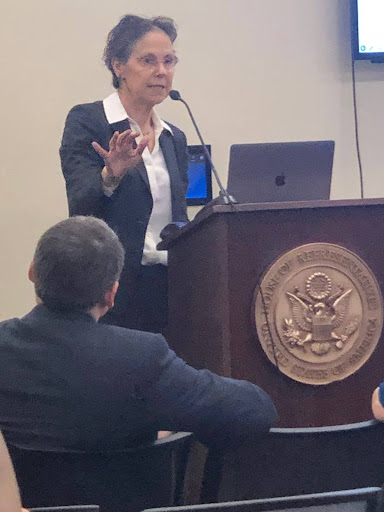

Anat got right to the heart of liquidity versus insolvency problems and the regulation of funding, noting that bank runs are an extreme form of liquidity problem. In theory, healthy banks can succumb to a run. But in reality, the banks most often subject to runs are opaque and have so much debt that depositors do not know what these banks’ true value is. Depositors might run if they suspect a bank may be insolvent.

“The market refers to companies that are insolvent or highly distressed as ‘zombies,’ the walking dead of the corporate world. Zombie banks display certain behaviors that would require companies in other sectors to file for bankruptcy. Yet a bank can hide its insolvency. As long as banks do not default, they can hide their insolvency more than other corporations. Banks show us they are not healthy by the ferocity of their fight against higher equity requirements.

Banks say equity is “expensive.” In fact, it is expensive and dangerous for society for banks to have too little equity. That is really where the conflict arises. The most “no-brainer” thing we can do for the system is ensure that society’s needs are satisfied and that the banks are less able to shift their costs and risks to others.” Anat continued, “the word “systemic” is the secret key to bailouts. A bail out means that a default is prevented by a third party. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, uninsured depositors were paid in full. On May 1, 2023, the depositors of First Republic Bank became depositors of JPMorgan Chase. The authorities, including the Federal Reserve, the FDIC, and the Department of the Treasury, claimed that no taxpayers paid for these arrangements. Someone made a promise that they could not keep, and a third party, the above agencies and the Treasury, came along to make sure the failing banks did not default on the depositors. Now, all the banks are paying for the failed banks that are no longer here and likely passing added costs to their customers. The idea that this is not a bail out is false. If these banks had much more equity that could absorb the losses, the failures and bailouts could have been prevented.”

Moderator Renita Marcellin observed, “In the media and on the hill, this idea of banks holding higher levels of capital seems so foreign. But most companies in other sectors do fund with greater equity levels and relatively speaking, less leverage.” She asked, “why have we allowed banks to run the way they run, and we accept it as a fact of life?” Anat responded. “What happened was, they were unstable and we added the safety net.”

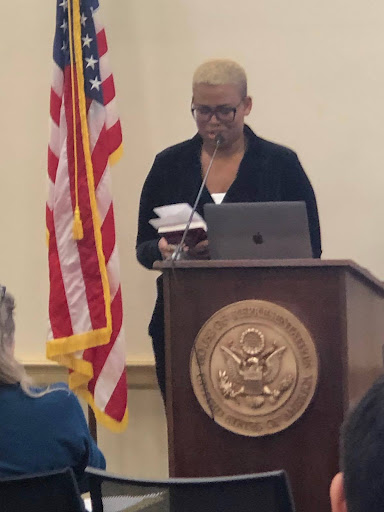

Jeremy Kress echoed Anat. “In a totally free market, if you go back to the early 1900s, creditors would demand that banks have very high equity for those creditors to leave their money there.

Jeremy Kress echoed Anat. “In a totally free market, if you go back to the early 1900s, creditors would demand that banks have very high equity for those creditors to leave their money there.

Jeremy shared parting thoughts about the main impacts of the proposal. “The vast majority of the capital increase would come from the largest banks’ market risk activities. More than two-thirds of the expected increase is attributable to those banks’ capital markets and trading, not regular lending activities. Much of the banks’ normal lending, such as credit cards and other retail lending, would come down under this proposal. The proposal is urgently necessary if you are concerned about the structure of the U.S. banking system and the top eight largest banks having too much power and being overweight in the system.”